Cover image credit: Johnson Wang.

Software products don’t exist in isolation. More products enter the market every day, and existing products need to rapidly learn, adapt, and anticipate the needs of their users to survive.

If you obsessively fixate on what other people have built, you end up with a “me-too” product that doesn’t solve the problem better than what’s already out there. If you ignore the competition to focus on your “great idea,” you end up blind to how people are currently solving the problem. You reinvent the wheel, and build what you think is cool rather than what your users need.

Competitor analysis helps you build software more intelligently. It allows you to rapidly test and validate product ideas by analyzing what other people are doing in your space. The key to this is approaching competitor analysis from a mindset of “non-competition.”

How to run “non-competitive” competitor analysis

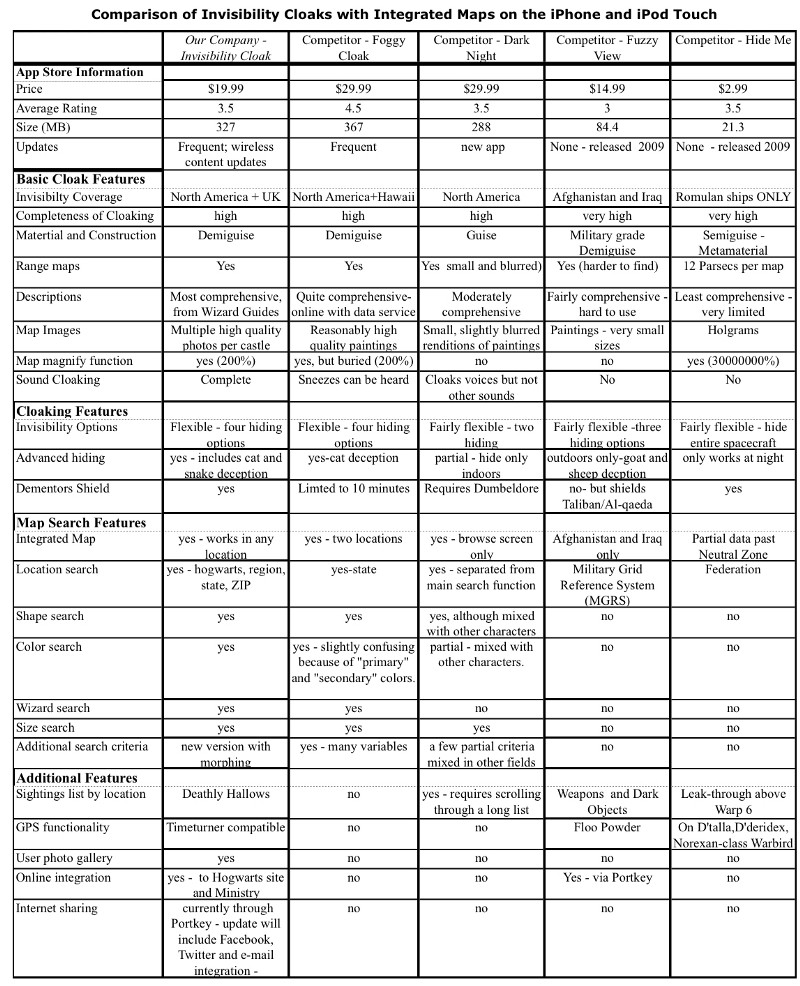

Lean Startup pioneer Steve Blank recounts an episode where a startup CEO brought him a competitor analysis table with a blow-by-blow teardown of every feature that every other product in the market had. As Blank points out, the problem with this type of thinking is it leads to the conclusion: “Our competitors have these features so our startup needs them too. Get to work and add all of these for first customer ship.”

Competitor analysis doesn’t work when looking at the competition becomes a proxy for digging into real users’ problems. Feature comparisons don’t make for good product specs. Having an overtly competitive mindset is likely to blind you to where you could actually help users to solve the problem better.

Whether you’re building a new product from scratch, or researching ways you can improve an existing product, you want to approach your analysis from a mindset of “non-competition.” That means you’re trying to root out your own internal biases and knee-jerk competitiveness to get a birds-eye view of the landscape — so you can find opportunities where the competition falls short.

We’ll walk through a three-step process of how you can run competitor analysis by identifying the competition, defining evaluation criteria, and drawing insights from analysis over time. By doing each of these things non-competitively, you’re better equipped to delve into customer needs, and figure out what’s working, what’s not, and what to do instead.

Identify the competition

In all likelihood, you have an idea of who your competition is before you get started with running user research or building a prototype. You’ve encountered competing companies online. You’ve talked to friends and customers about products they’ve used in the past. That’s the bare minimum you need to get started.

But identifying the competition is about more than just putting a name to the competition. It’s about getting insights into your users and the problems that they’re trying to solve.

You don’t just want a list of products that are similar to yours. If you’re building a team chat tool, for example, you might compete with tools like Slack and HipChat — but you also might compete with other forms of communication like email or messaging forums.

Break your competition into two categories:

-

Direct Competitors are companies that solve the same problem, have the same core functions, and an overlapping user base. Direct competitors are typically the focus of competitor analysis. If you’re building a chat tool, your direct competitors would be companies like Slack, HipChat, and Campfire.

-

Indirect Competitors either solve a different problem for the same customer base, or solve a similar problem for a different customer base. If you’re building a chat tool, indirect competitors would include email, Google Groups and potentially companies like Skype or Trello.

It’s important to get a good spread of both direct and indirect competitors. Direct competitors offer a lens into how you could do better and make more revenue today because that’s who potential customers are spending your money with today. Indirect competitors help reveal opportunities down the line — while they’re not targeting your immediate customer base, or problem, they cover areas adjacent to your product where you might expand in the future.

You can identify direct and indirect competition by searching for specific keywords in Google, or by using Google’s Keyword Explorer. Then, dig deeper. Go to places like Stackshare and Siftery to see what products people in your space are using. Get on places where users are spending time like Quora or Twitter, and talk to them directly.

Ask them the following questions:

-

What products do you currently use?

-

How happy are you with the products you use and their features?

-

Do you use multiple products or tools to solve the same problem?

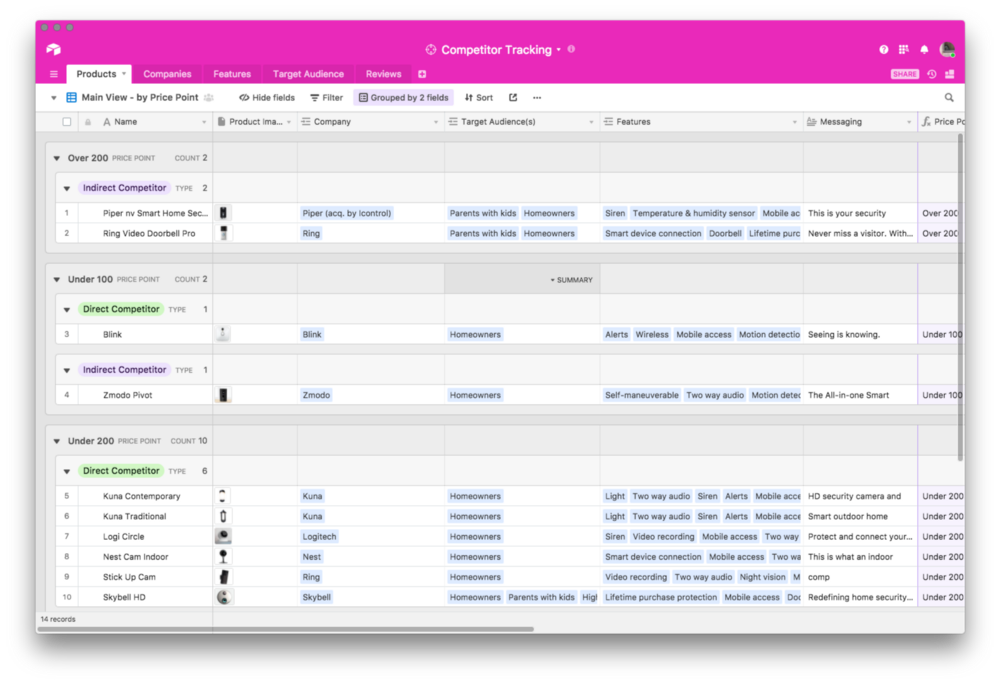

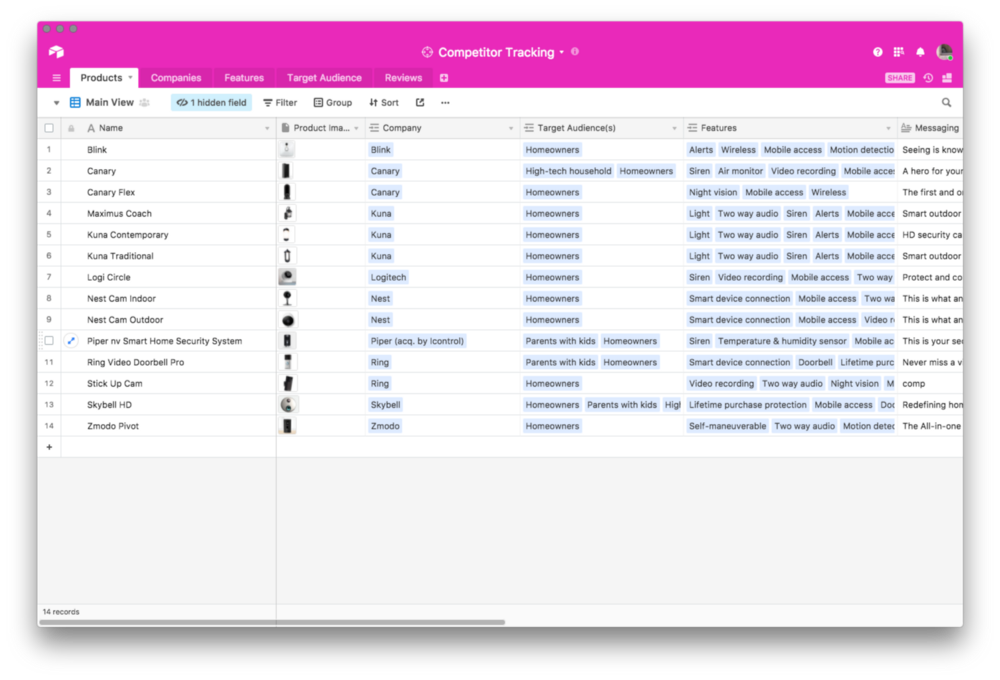

Create a list of 5–10 competitors and organize them according to categories like competitor type and pricing.

Define the criteria for evaluation

In your competitor analysis, you won’t be able to monitor *everything *the competition is doing across their website design, marketing collateral, blog content, and social media. Running an effective analysis is all about how you narrow the field by figuring out the right criteria to use to evaluate the competition.

Customers don’t buy features, they usually buy something that solves a real or perceived need. That’s the comparison you and your investors should be looking at — what do customers say they need or want?

That doesn’t simply mean listing out features of competing products for a blow-by-blow comparison. Select criteria that will provide you with more context around what they’re building, who they’re building it for, and how they’re reaching users through marketing and design. As Steve Blank says: Customers don’t buy features, they usually buy something that solves a real or perceived need. That’s the comparison you and your investors should be looking at — what do customers say they need or want?

By breaking down qualitative and quantitative data around the competition, you’re forming deeper intuitions around how your target audience’s needs are being met — and how you can go even deeper.

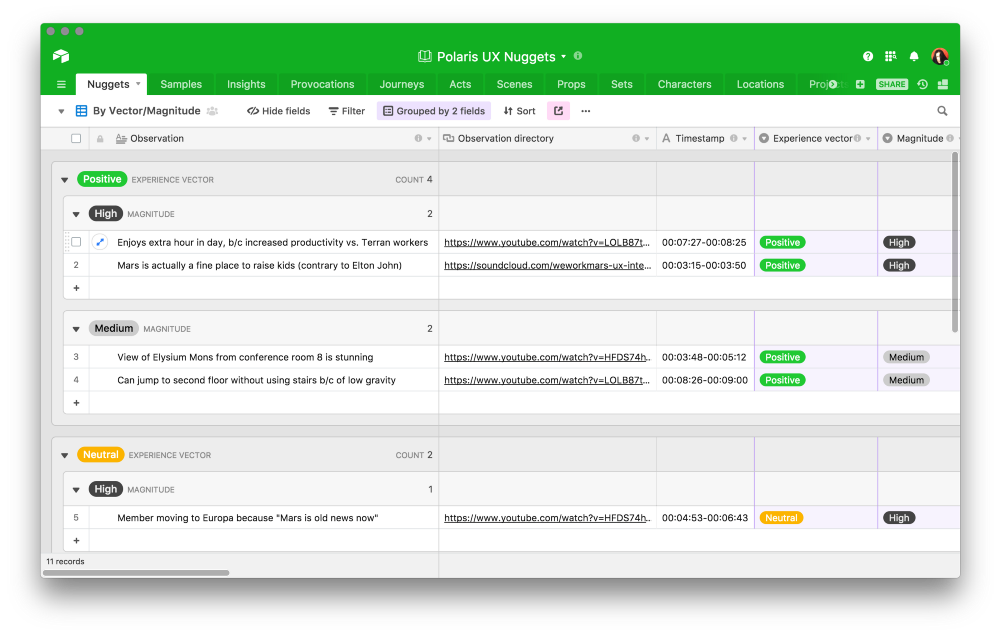

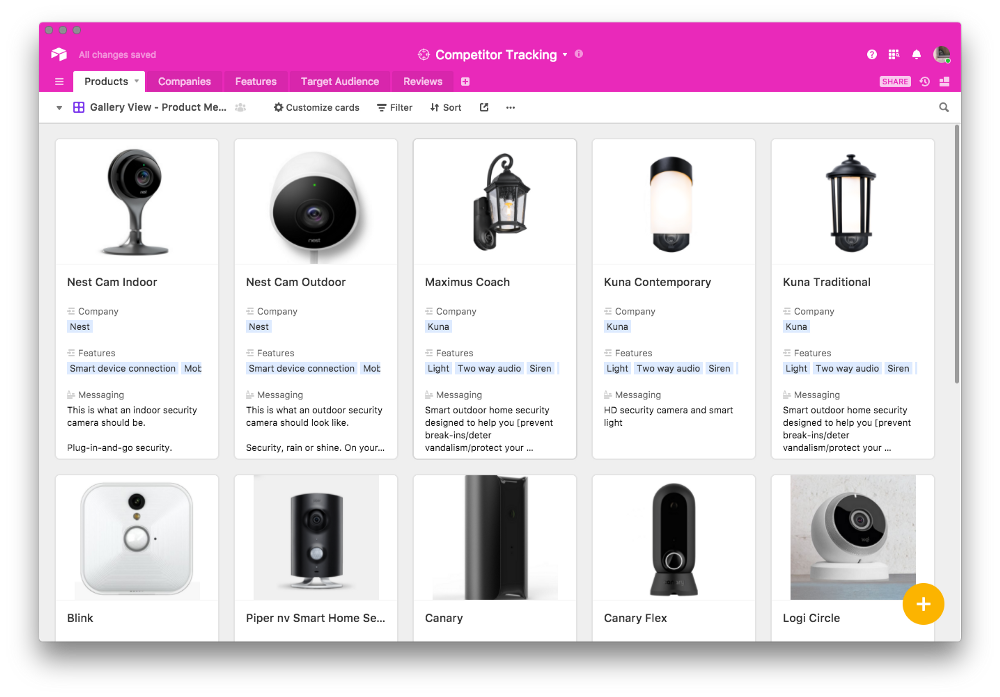

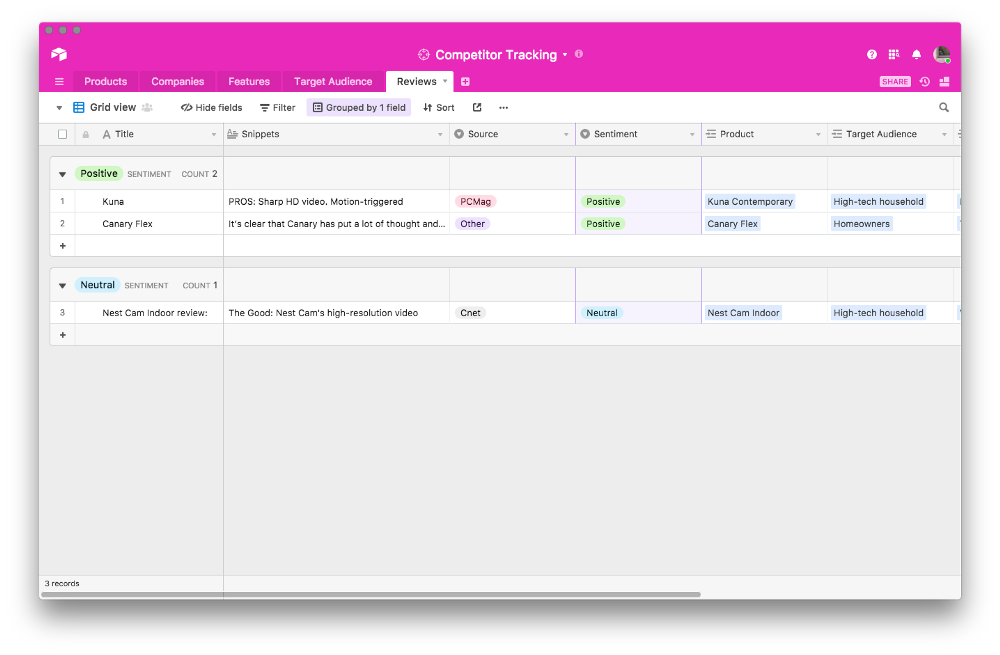

In the sample Airtable base above, we’re using the following criteria to evaluate competing products:

-

Company

-

Target Audience

-

Features

-

Messaging

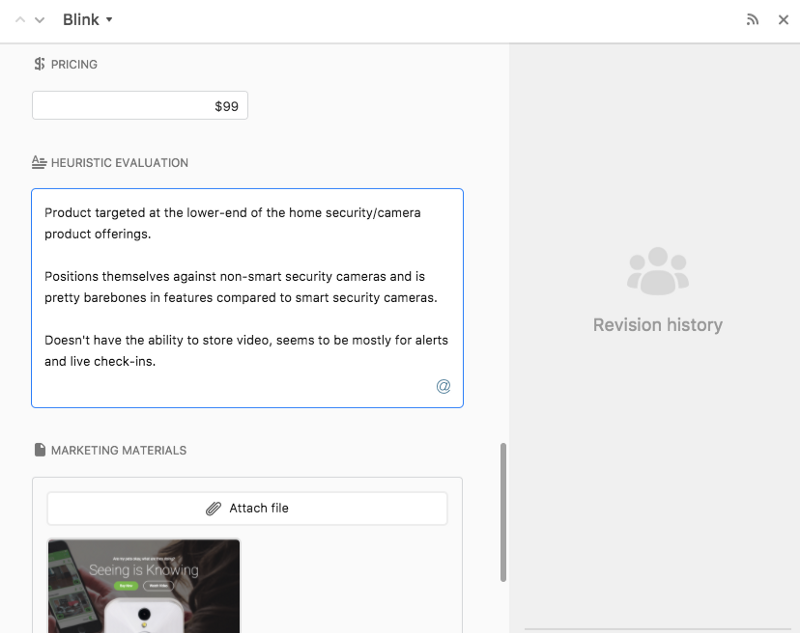

Once you have a set of criteria, you can also add a long-form notes field to fill in with heuristic evaluations of products along those axes.

A heuristic evaluation simply means judging the product according to the criteria that you’ve outlined above. It helps you make judgement calls on competing products and how it relates to what you’re building.

Organize the information

The final part of running your competitor analysis is devising a way to structure the data that makes your analysis easy to update and mine for insights over time — and also easy for members of your team to reference and cross-check it with what they’re building.

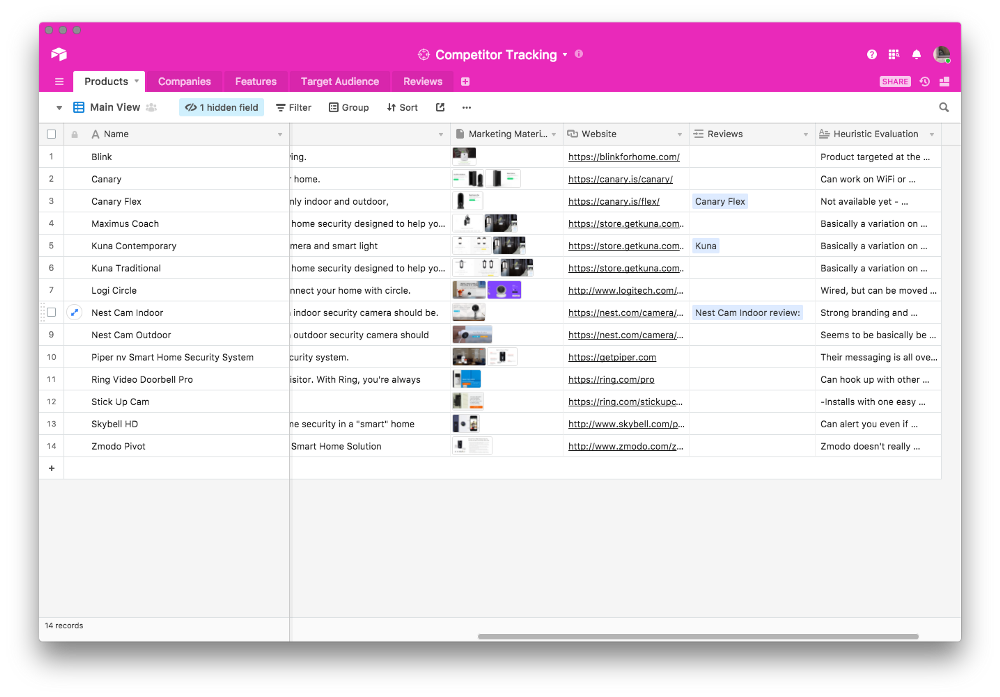

Once you have the basic criteria you’re using to evaluate the competition, there are a variety of places you can look to use as a springboard for your evaluation. By keeping these in a single place, you make it easy to update your analysis with new research over time.

-

Competitor websites & marketing collateral: Website copy, design and marketing collateral in the form of white papers and content can tell you a lot about how a specific company is positioning themselves in the market.

-

3rd party sources: Search community forums like Reddit and ProductHunt as well as review websites to see what users are saying about the competition.

-

User interviews & usability tests: Find users to test within your network, or use a tool like UserTesting.com, which sources interviewers for you. In our sample competitor tracking database, we’re drawing conclusions based on the website and marketing material from competing products.

In our sample competitor tracking database, we’re drawing conclusions based on the website and marketing material from competing products:

Having all this information in a single place makes it easy to create views that are most helpful to respective members of your team.

Product positioning and messaging

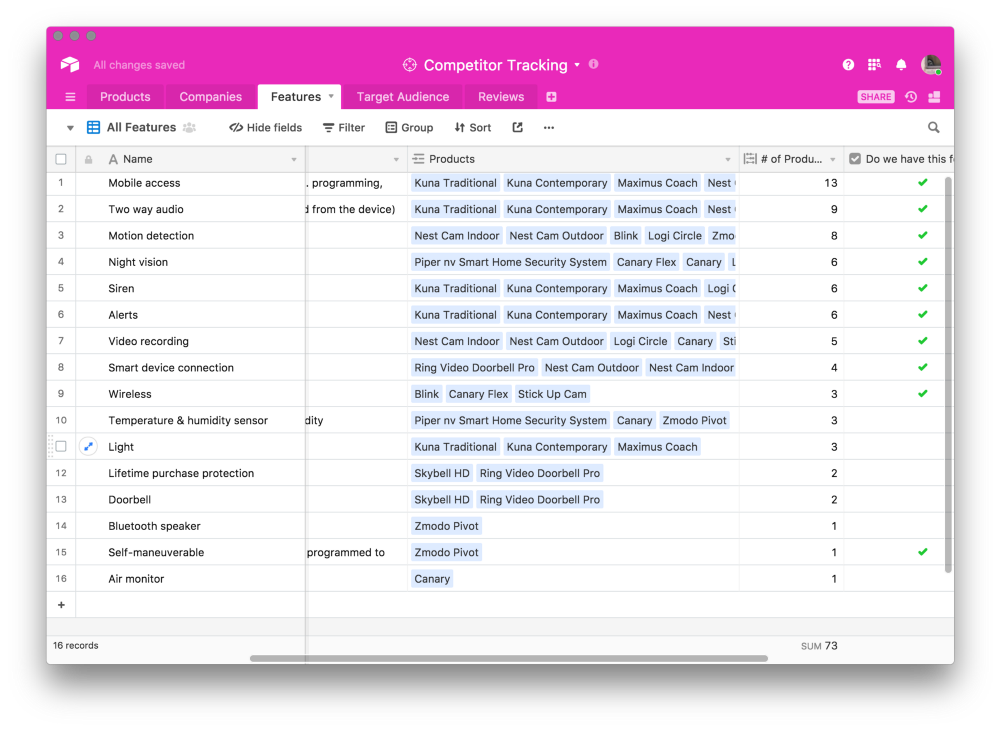

Feature comparison

The following view lists the total number of features encountered in the analysis, and is sorted by the number of products within each feature.

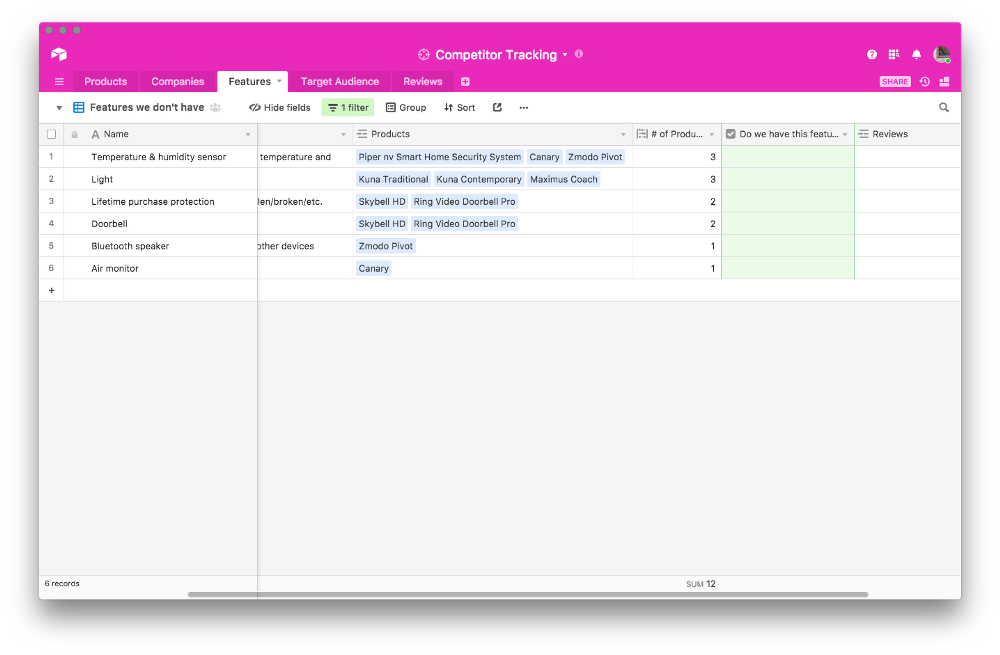

…and feature gaps

Once you have that, your product team might create a separate view that includes only features your product doesn’t offer:

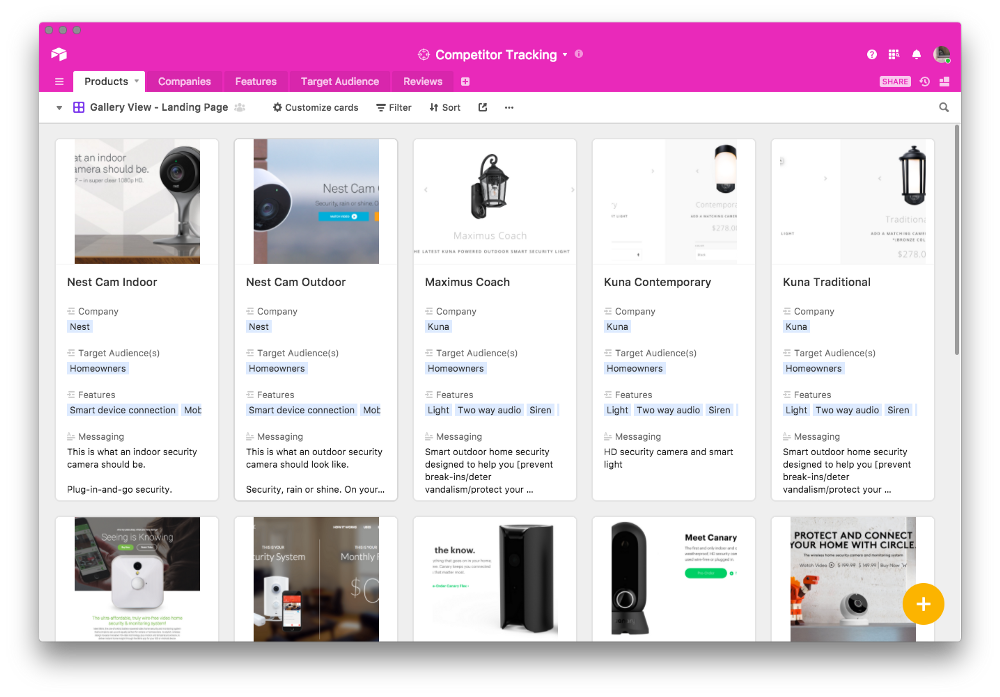

Landing page analysis

Not only is it important to get a sense of what other products do, you also want to see how they’re being targeted at their intended audience. Your marketing team might mock together a view that organizes competing products by landing page:

Review tracking

This view organizes 3rd party reviews into three categories: “Positive,” “Neutral,” and “Negative.”

Hit the ground running: competitor analysis templates

Now that you’re equipped with an understanding of how to run a competitor analysis, it’s time to get started on your own. Below, we’ve included templates in Airtable that real companies have used to monitor the competition. Play around with them, mix and match, and borrow!

Yext’s Incident Tracker

Yext, a company that centralizes business listing data across the internet, uses a base in Airtable to monitor the competition.

In the “Companies” table, Yext keeps tabs on competing companies, monitoring comparable features, and company information. A separate “Incidents” table is linked to the Companies table with specific noteworthy events — for example, a writeup of a competitor in TechCrunch, or a new feature launch.

As Yext’s VP of Product Jonathan Kennell points out: “The philosophy of your business and how you actually model that in processes and technology is always changing….You can’t just set your systems up once and assume they’ll still work years — or even months — later.”

You can’t just set your systems up once and assume they’ll still work years — or even months — later.

Take Yext’s Competitor Analysis Tracker base for a test drive here!

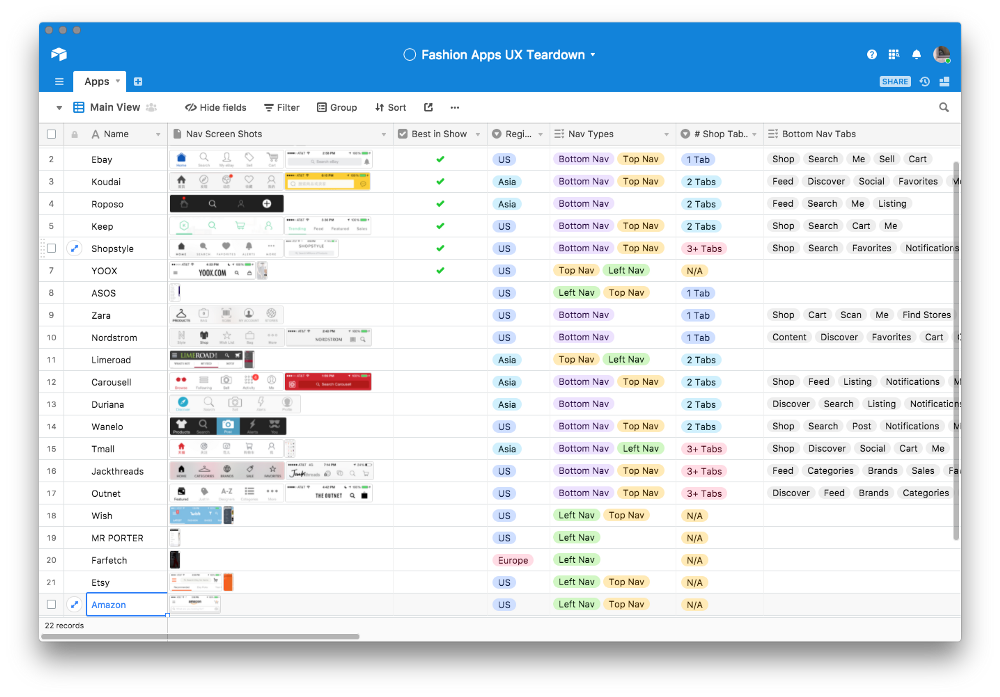

UX Teardown Template

For specific product launches or redesigns, you’ll want to dig deeper into specific UX elements in your competitor analysis.

While preparing to design a shopping flow for an e-commerce app from the ground up, Melanie Oei put together an extensive database of 22 different competitors:

The base documents major design decisions around each app, focusing on navigation hierarchy and search flow. It also includes screenshots of specific UX elements like navigation bars, drop-down menus, and search bars.

Competition today

People building products today have to deal with an increasing amount of competition. It’s easier to write code, and faster to deploy it. Simply focusing on what you want to build ignores the bigger issue of how you can best solve a problem for users.

Take something like Instagram’s imitation of Snapchat. Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom never denied looking to Snapchat for inspiration when adapting Stories: “It would be crazy if we saw something that worked with consumers that was in our domain and we didn’t decide to compete on it.”

As Systrom says, “You can trace the roots of every feature anyone has in their app, somewhere in the history of technology.”