Wikitongues is on a mission to preserve every language in the world.

Of the 7,000 living languages in the world, roughly half are expected to disappear by the year 2100. To Frederico Andrade, co-founder of grassroots nonprofit Wikitongues, each extinction is a partial loss of the world’s cultural landscape; some stories and ideas are simply inexpressible outside their native languages. Take, for instance, Pirahã, an Amazonian language that never developed specific words for colors. The comparisons (“this looks like blood”) that help speakers of Pirahã to describe everyday items and interactions represent a fundamentally different and more complex way of looking at the world around them. Similarly unmatched in more broadly spoken languages are the time-of-day-dependent verb conjugations of the New Guinean language Berik. These unique perspectives not only enrich and broaden our collective understanding, but form a fundamental component of native speakers’ identities. To Andrade, protecting the language rights of these diverse linguistic communities is an urgent mission.

Wikitongues is at the forefront of the global effort to preserve these linguistic traditions, aiming to raise awareness of endangered languages and advocate for their protection. Since its founding in 2014, the small army of globally distributed contributors have identified and recorded more than 300 videos of native speakers holding forth in 193 distinct languages. The project serves as a combination of an archive, a basic reference for language learners, and a way of introducing obscure languages to the broader public. Airtable is used as their central repository for all of the videos, volunteers, reference information, and programs that comprise the Wikitongues project.

All the world’s languages, at a glance

The core of the primary Wikitongues Airtable base is a series of five linked tables — ‘Languages’, ‘Nations’, ‘Territories’, ‘Continents’, and ‘Writing Systems — that collectively provide a comprehensive look at every single known language in the world. The team collects exhaustive background information about each language, carefully identifying and cataloging each different name a single language might have, the nation in which it originated, its primary writing system, and more.

The central table to which the others are linked is the ‘Languages’ table.

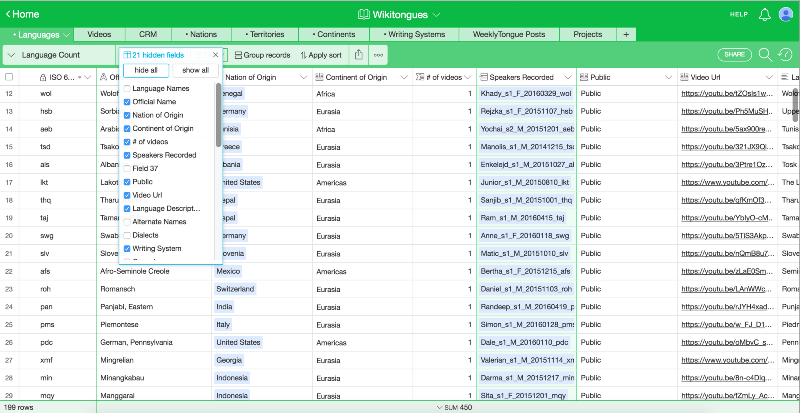

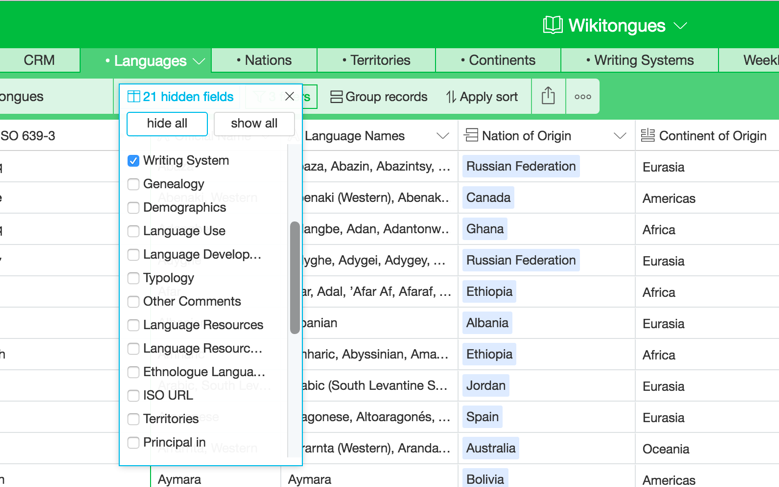

To get a clear snapshot of how many videos are available per language, the Wikitongues team maintain a “Language Count” view. In this view, 21 fields are hidden so that it is easy to see at a single glance the language name, nation and continent of origin, # of videos, and linked records associated with each of the videos.

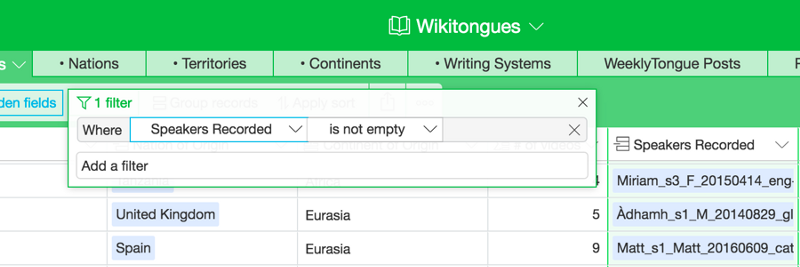

They also apply a filter to this view that hides any languages that don’t currently have at least one recorded video.

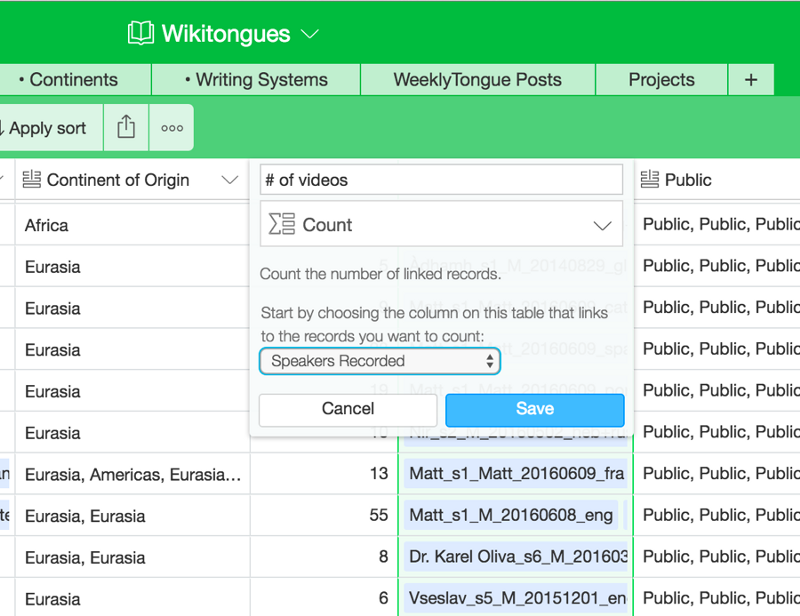

Displaying the most crucial piece of information for this view — the total number of videos for each language — is simplified by setting the ‘# of videos’ field as a count field, which automatically tallies the total number of linked records in the ‘Speakers Recorded’ field.

A view for every project

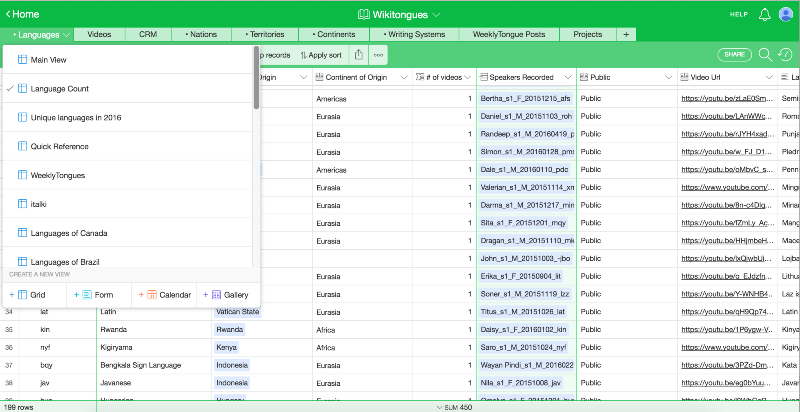

Because this table is used as a central reference for so many of the activities the team undertakes, they’ve created a wide range of other views as well. At last count, there were 26 views (and the number continues to grow.)

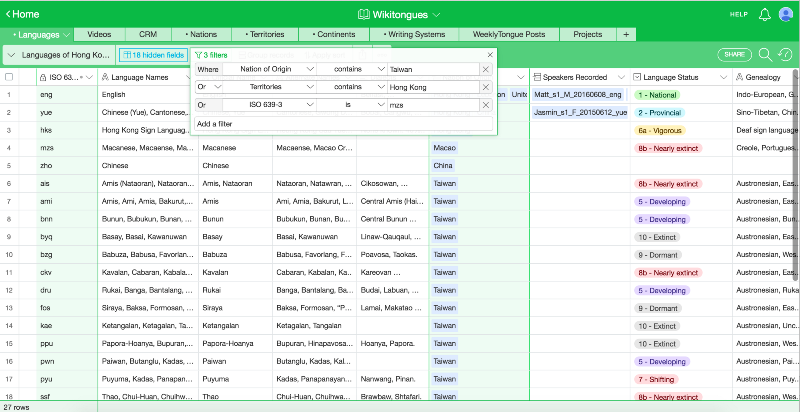

When for an editorial project they need to work with only the records for a particular family of languages, they create a view like “Languages of Hong Kong and Taiwan.” The team wants to compare only the languages indigenous to Hong Kong and Taiwan as part of this project, focusing especially on information such as alternative names for each language, their genealogies, and the demographics of the people who speak them. To achieve this type of focus, they first filter the view to display only the nations or territories in question. They then identify the fields that correspond with the points they wish to make in their post, and set up the view to hide 18 irrelevant fields (including the “# of videos” count field that was essential in the “Language Count” view.

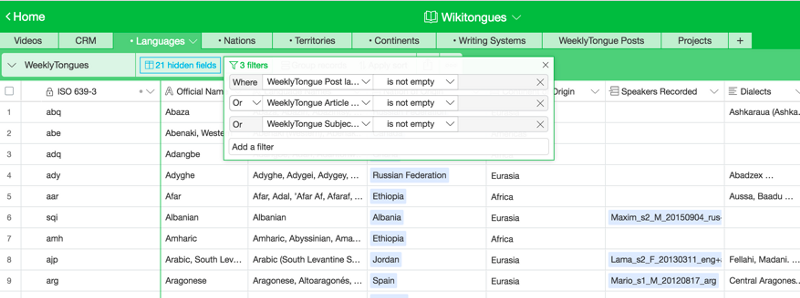

The “WeeklyTongues” view, on the other hand, served to facilitate the creation of a weekly blog post series last year. Each post featured a single language in some depth, which required an entirely different subset of the fields and records. For these posts, Frederico and team aimed to provide an intriguing introduction to a language that their readers will likely never have previously encountered.

To get started, the post writer first requires a quick reference for which languages have already been profiled, which is achieved using three filters:

From there, only a few high level background details are necessary to provide the overview that will engage their audience — instead, it’s important for the view to surface links to additional language learning resources that will allow readers to learn more. This view ultimately hides 21 other fields that will only distract the writer while preparing the post:

One nation, many languages

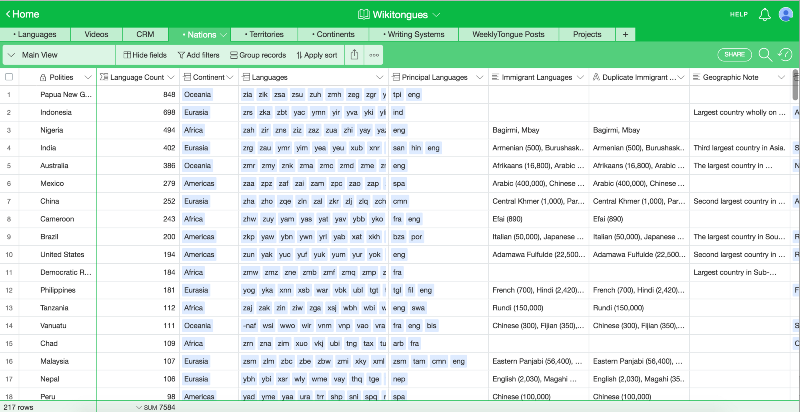

To get a better look at the languages of a particular country, the team has two different options: they can either use saved views like the “Languages of Hong Kong and Taiwan,” or they can switch to the linked ‘Nations’ table, which contains substantially more background information about the countries in question.

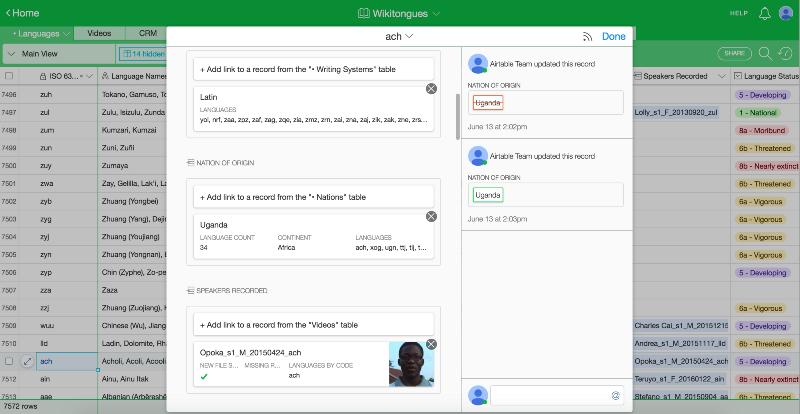

Because the tables are linked, any time a new language, such as Acholi, is added to the ‘Languages’ table and its nation is selected, that new language shows up in the linked record field for the corresponding nation — in this case, Uganda — along with other linked languages.

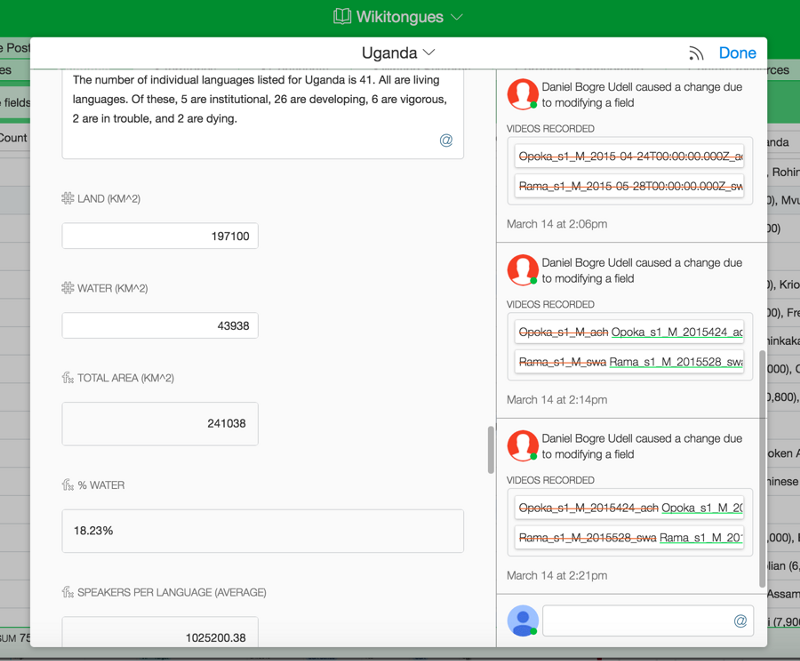

To capture the full context and richness of the language landscape of the included nations, the Wikitongues team has assembled a panoply of additional details, including the principal languages of that country, the primary languages spoken by the most common immigrants to the country, the size and resources of the nation, population, and number of languages spoken.

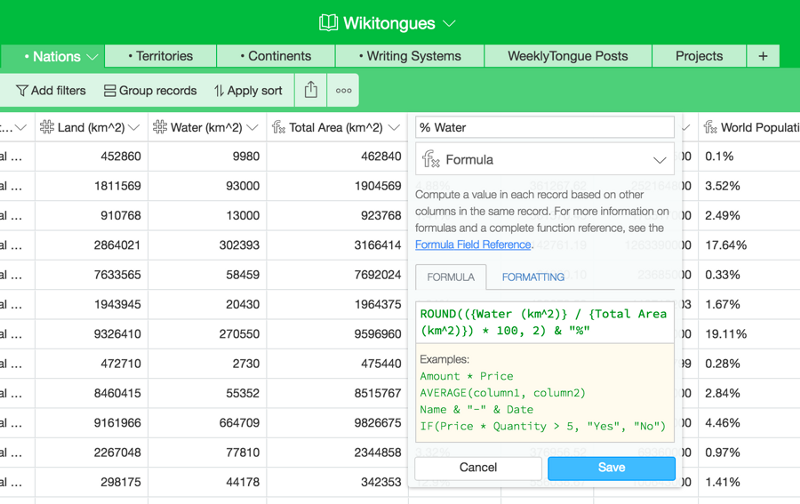

This table also uses a number of formula fields to help provide more meaningful context from the raw numbers, calculating things like the percent of the country that is water, or the percent of the total world population that lives in that nation.

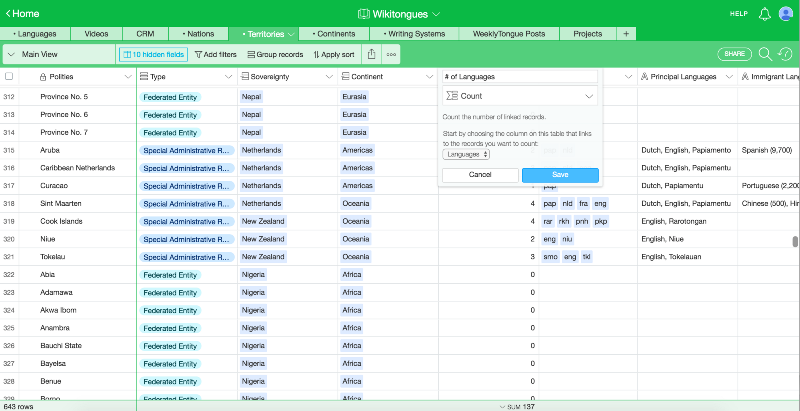

When dealing with special regions that for historical, demographic, or political reasons are more appropriately considered independently from their official sovereign nations, the Wikitongues team turns to the ‘Territories’ table. Though it showcases much of the same information as the ‘Nations’ table, by using a linked table here, the team can not only use a multiple select field to classify the type for each region, but can also use a count field to automatically tally the total number of languages in that region, all while still maintaining clear linked relationships with their sovereign nations and the continent in which they are found.

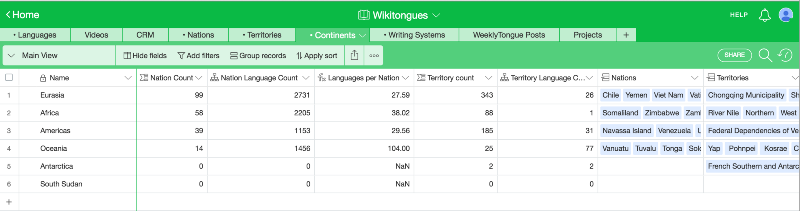

Similar techniques are used in the ‘Continents’ table, which provides a high level view of total language activity by continent. Though this table (unsurprisingly) only has a few records, it relies heavily on count, rollup, and formula fields to aggregate the information from each continent’s respectively linked ‘Nations’ and ‘Territories’ records.

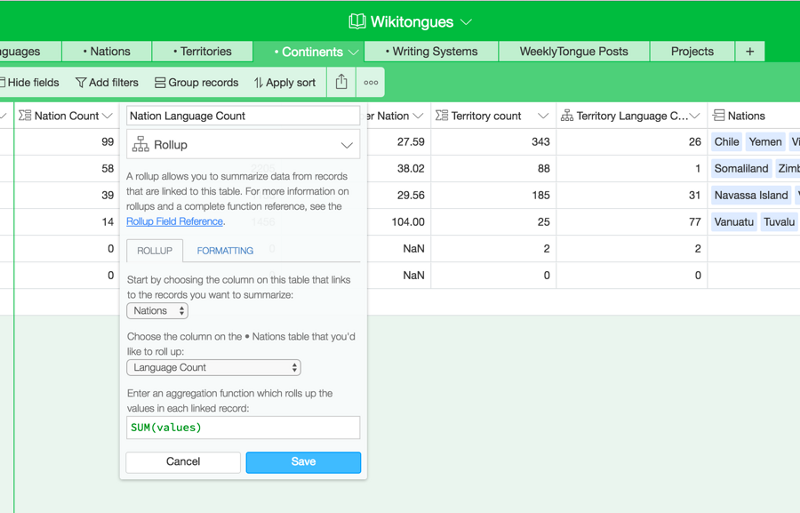

To calculate the total number of languages per nation instantly and without any additional data entry required, the Wikitongues team uses a rollup field. Rollup fields allow you to perform a function on the contents of a specific field in a set of linked records.

In this case, the Wikitongues team is simply adding up the number of linked languages per nation in that continent:

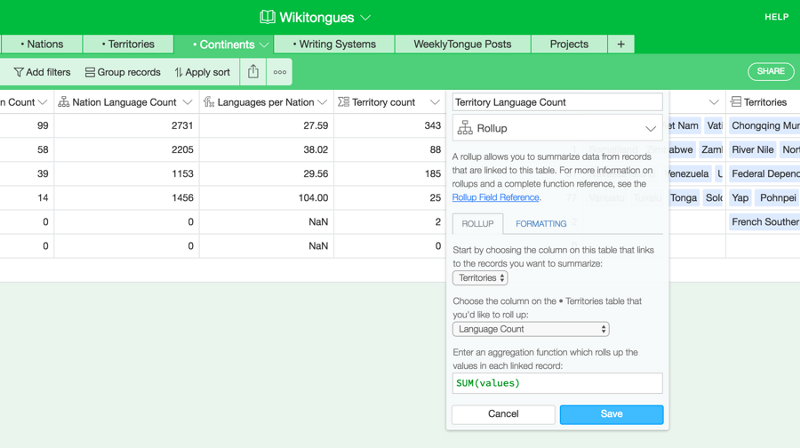

They use the same approach to get the total number of languages per territory in that continent:

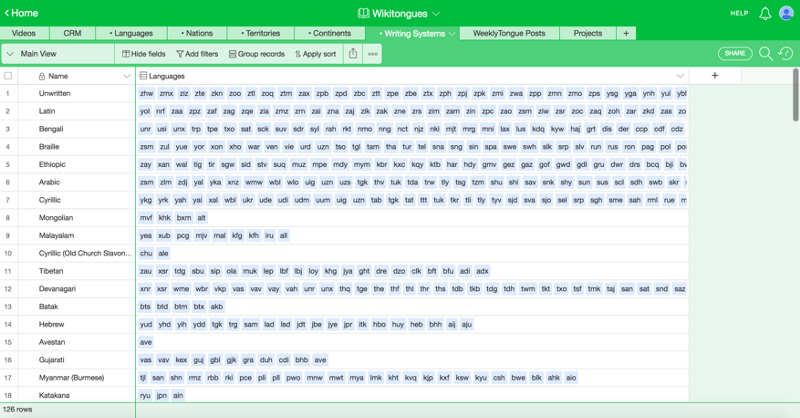

The write system

The writing system used by a language adds another level of complexity to the understanding of the language, not least because multiple languages might share the same system (and that relationship often has broad linguistic implications). As a result, although it could otherwise be covered by simply making a ‘Writing systems’ multiple select field in the central ‘Languages’ table, the Wikitongues team chooses to break it out into its own linked table.

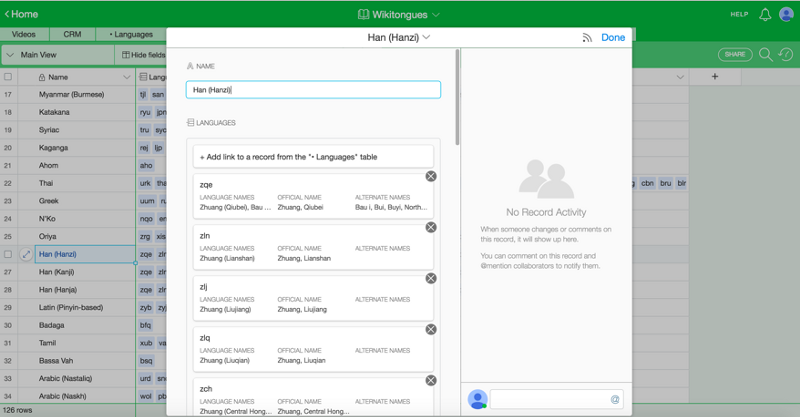

This approach allows team members to rapidly see both which languages use a particular writing system and which writing systems are most popular relative to the others, something that would be difficult to see by simply using filters in the ‘Languages’ table. This is particularly useful for related writing systems such as the three variations of Han or the two variations of the Arabic writing system.

What’s more, if a team member wants to get a bit more information about each language that uses a writing system without having to wade through all the fields in the ‘Languages’ table, they can just expand the record for the writing system by hitting the space bar:

The five linked tables of the language reference provide the backbone for much of the Wikitongues project, helping to inform everything from their content and sponsorship efforts. It also insures that the entire, geographically dispersed team remains on the same page and makes decisions based on the same information.

To learn how these materials directly drive and enable the operations of their nonprofit — all within Airtable — check out part two.